“ … the wild and lawless countries between the Adriatic and Black Seas.” ‘Through Savage Europe’, 1907, reprinted 1913

“Why ‘savage’ Europe?” asked a friend who recently witnessed my departure from Charing Cross for the Near East. “Because,” I replied, “the term accurately describes the wild and lawless countries between the Adriatic and Black Seas.”

So begins Harry De Windt’s narrative of his journey through the Balkans in 1907. Having stepped off the steamer in Cattaro, (Kotor) Montenegro, “the tiny principality which has proved such a thorn in the side of the Turk” , De Windt goes on to report back to the Westminster Gazette from Bosnia, Herzegovina, Servia (Serbia), Bulgaria and Rumania (Romania) before embarking for Southern Russia and the Caucasus.

Only some 5 years before the Balkan Wars and seven before that infamous shooting of Franz Ferdinand by Gavrilo Princip in Sarajevo “most Englishmen (were) less familiar with the geography of the Balkan States than with that of Darkest Africa”.

This lack of consideration for those ‘savage’ lands was soon to change with the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in the Balkan Wars of 1912 and 1913 and the loss of almost all of ‘Turkey-in-Europe’. The consequent increasing confidence of Serbia and increasing paranoia of Austria-Hungary set the stage for the 1914 crisis.

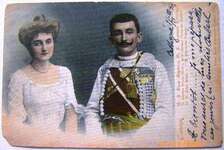

Meanwhile, life in the Balkans itself, even amongst some of the more privileged players, was too complicated to understand. Poor Prince Mirko of Montenegro, pictured here in 1903, failed to get his seat on the Serbian throne despite his Obrenović marriage. The notorious defenestration of Alexander and Draga conferred the crown on Peter Karadjordjević (Karadjordjevic) that very year. Mirko divorced his Natalija in 1917 and ended up in Vienna.

Bibliography: background to war: For a complete list of publications on the dual monarchy, F. R. Bridge’s ‘Critical Bibliography – The Habsburg Monarchy’ reaches back to 1804.

Literature on the last years of Austria-Hungary , the ‘sick man of Europe’ and the dissolution of the dual monarchy are legion but A. J. P. Taylor’s (‘The Habsburg Monarchy 1815-1918’) provocative exploration of the hundred years leading up to World War One has remained a standard text. Arthur J. May’s considerable erudition and extensive use of sources takes two volumes to explore “The Passing of the Hapsburg Monarchy 1914-1918” – this work a sequel to his “Hapsburg Monarchy 1867 – 1914”.

Harry de Windt was not the only roving journalist to penetrate the Balkans in search of adventure in the early days of the 20th century. Possibly even at the same time, John Foster Fraser, author, special correspondent for Allied Newspapers and celebrity cyclist for Rover safety bicycles (Fraser cycled around the world in 1896, covering 19,237 miles in 774 days) found himself in Macedonia in 1905. More astute than De Windt, his ‘Pictures from the Balkans’ (1906) in the very first chapter reveal the entrenched problems created by the Great Powers in this unstable area. Reissued in 1912, a ‘popular’ edition of Fraser’s book on the Balkans includes the note that “the publishers have not thought it necessary to make any alterations in the Author’s graphic and far-seeing text”.

A number of contemporary experts did try to explain the Balkans to an Anglophone public and one of the best known is William Miller, expert on Russia and Slavonic subjects generally. His ‘The Balkans’ in The Story of the Nations series published in 1896, likens the area to the Low Countries in the Middle Ages. Miller explains that “the mutual jealousies of Bulgarian and Serb, the struggle of various races for supremacy in Macedonia … the friendship and enmity of Russian and Turk … have their root deep down in the past annals of the Balkan lands. He conscientiously starts in Dacia in 106 A. D..